History of Nigeria

The history of Nigeria can be traced to prehistoric settlers (Nigerians) living in the area as early as 1100 BC. Numerous ancient African civilizations settled in the region that is today Nigeria, such as the Kingdom of Nri, the Benin Empire, and the Oyo Empire. Islam reached Nigeria through the Borno Empire between (1068 AD) and Hausa States around (1385 AD) during the 11th century,[clarification needed] while Christianity came to Nigeria in the 15th century through Augustinian and Capuchin monks from Portugal. The Songhai Empire also occupied part of the region.

The history of Nigeria has been crucially impacted by the Transatlantic Slave Trade,[1] which started in Nigeria in the late 15th century. At first, Europeans captured Nigerians who lived in coastal communities. Later, they used local brokers to provide them with slaves. This dynamic escalated conflicts among the different ethnic groups in the region and disrupted older trade patterns through the Trans-Saharan route.[2]

Lagos was invaded by British forces in 1851 and formally annexed in 1861. Nigeria became a British protectorate in 1901. Colonization lasted until 1960, when an independence movement succeeded in gaining Nigeria its independence. Nigeria first became a republic in 1963, but succumbed to military rule three years later after a bloody coup d'état. A separatist movement later formed the Republic of Biafra in 1967, leading to the three-year Nigerian Civil War. Nigeria became a republic once again after a new constitution was written in 1979. However, the republic was short-lived, when the military seized power again four years later. A new republic was planned to be established in 1993, but was dissolved by General Sani Abacha. Abacha died in 1998 and a fourth republic was later established the following year, which ended three decades of intermittent military rule.

Early history[edit]

Archaeological research, pioneered by Charles Thurstan Shaw has shown that people were already living in south-eastern Nigeria (specifically Igbo Ukwu, Nsukka, Afikpo and Ugwuele) 100,000 years ago. Excavations in Ugwuele, Afikpo and Nsukka show evidence of long habitations as early as 6,000 BC. However, by 9th Century AD, it seemed clear that the Igbos had settled in Igboland. Shaw's excavations at Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria revealed a 9th-century indigenous culture that created highly sophisticated work in bronze metalworking, independent of any Arab or European influence and centuries before other sites that were better known at the time of discovery.

The earliest known example of a fossil human skeleton found anywhere in West Africa, which is 13,000 years old, was found at Iwo-Eleru in Isarun, western Nigeria and attests to the antiquity of habitation in the region.[3]

Microlithic and ceramic industries were also developed by savanna pastoralists from at least the 4th millennium BC and were continued by subsequent agricultural communities. In the south, hunting and gathering gave way to subsistence farming around the same time, relying more on the indigenous yam and oil palm than on the cereals important in the North.

The stone axe heads, imported in great quantities from the north and used in opening the forest for agricultural development, were venerated by the Yoruba descendants of Neolithic pioneers as "thunderbolts" hurled to earth by the gods.[3]

Iron smelting furnaces at Taruga dating from around 600 BC provide the oldest evidence of metalworking in Sub-Saharan Africa. Kainji Dam excavations revealed iron-working by the 2nd century BC. The transition from Neolithic times to the Iron Age apparently was achieved indigenously without intermediate bronze production. Others suggest the technology moved west from the Nile Valley, although the Iron Age in the Niger River valley and the forest region appears to predate the introduction of metallurgy in the upper savanna by more than 800 years. The earliest identified iron-using Nigerian culture is that of the Nok culture that thrived between approximately 900 BC and 200 AD on the Jos Plateau in north-eastern Nigeria. Information is lacking from the first millennium AD following the Nok ascendancy, but by the 2nd millennium there was active trade from North Africa through the Sahara to the forest, with the people of the savanna acting as intermediaries in exchanges of various goods.

Hausa Kingdoms[edit]

The Hausa Kingdoms were a collection of states started by the Hausa people, situated between the Niger River and Lake Chad. Their history is reflected in the Bayajidda legend, which describes the adventures of the Baghdadi hero Bayajidda culminating in the killing of the snake in the well of Daura and the marriage with the local queen magajiya Daurama. while the hero had a child with the queen, Bawo, and another child with the queen's maid-servant, Karbagari.[4]

Sarki mythology[edit]

According to the Bayajidda legend, the Hausa states were founded by the sons of Bayajidda, a prince whose origin differs by tradition, but official canon records him as the person who married the last Kabara of Daura and heralded the end of the matriarchal monarchs that had erstwhile ruled the Hausa people. Contemporary historical scholarship views this legend as an allegory similar to many in that region of Africa that probably referenced a major event, such as a shift in ruling dynasties.

==='yan'uwa Bakwai=(seven brothers)

According to the Bayajidda legend, the Banza Bakwai states were founded by the seven sons of Karbagari ("Town-seizer"), the unique son of Bayajidda and the slave-maid, Bagwariya. They are called the Banza Bakwai meaning Bastard or Bogus Seven on account of their ancestress' slave status.

- Zamfara (state inhabited by Hausa-speakers)

- Kebbi (state inhabited by Hausa-speakers)

- Yauri (also called Yawuri)

- Gwari (also called Gwariland)

- Kwararafa (the state of the Jukun people)

- Nupe (state of the Nupe people)

- Ilorin(was founded by the Yoruba)

Hausa Bakwai[edit]

The Hausa Kingdoms began as seven states founded according to the Bayajidda legend by the six sons of Bawo, the unique son of the hero and the queen Magajiya Daurama in addition to the hero's son, Biram or Ibrahim, of an earlier marriage.

The states included only kingdoms inhabited by Hausa-speakers:

Since the beginning of Hausa history, the seven states of Hausaland divided up production and labor activities in accordance with their location and natural resources. Kano and Rano were known as the "Chiefs of Indigo." Cotton grew readily in the great plains of these states, and they became the primary producers of cloth, weaving and dying it before sending it off in caravans to the other states within Hausaland and to extensive regions beyond. Biram was the original seat of government, while Zaria supplied labor and was known as the "Chief of Slaves." Katsina and Daura were the "Chiefs of the Market," as their geographical location accorded them direct access to the caravans coming across the desert from the north. Gobir, located in the west, was the "Chief of War" and was mainly responsible for protecting the empire from the invasive Kingdoms of Ghana and Songhai.

Islam arrived to Hausaland along the caravan routes. The famous Kano Chronicle records the conversion of Kano's ruling dynasty by clerics from Mali, demonstrating that the imperial influence of Mali extended far to the east. Acceptance of Islam was gradual and was often nominal in the countryside where folk religion continued to exert a strong influence. Nonetheless, Kano and Katsina, with their famous mosques and schools, came to participate fully in the cultural and intellectual life of the Islamic world. The Fulani began to enter the Hausa country in the 13th century and by the 15th century, they were tending cattle, sheep, and goats in Borno as well. The Fulani came from the Senegal River valley, where their ancestors had developed a method of livestock management based on transhumance. Gradually they moved eastward, first into the centers of the Mali and Songhai empires and eventually into Hausaland and Borno. Some Fulbe converted to Islam as early as the 11th century and settled among the Hausa, from whom they became racially indistinguishable. There they constituted a devoutly religious, educated elite who made themselves indispensable to the Hausa kings as government advisers, Islamic judges, and teachers.

Zenith[edit]

The Hausa Kingdoms were first mentioned by Ya'qubi in the 9th-century[citation needed] and they were by the 15th-century vibrant trading centers competing with Kanem-Bornu and the Mali Empire.[5] The primary exports were slaves, leather, gold, cloth, salt, kola nuts, animal hides, and henna. At various moments in their history, the Hausa managed to establish central control over their states, but such unity has always proven short. In the 11th-century, the conquests initiated by Gijimasu of Kano culminated in the birth of the first united Hausa Nation under Queen Amina, the Sultana of Zazzau but severe rivalries between the states led to periods of domination by major powers like the Songhai, Kanem and the Fulani.

Yoruba[edit]

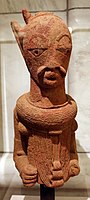

Historically the Yoruba people have been the dominant group on the west bank of the Niger. Their nearest linguistic relatives are the Igala who live on the opposite side of the Niger's divergence from the Benue, and from whom they are believed to have split about 2,000 years ago. The Yoruba were organized in mostly patrilineal groups that occupied village communities and subsisted on agriculture. From approximately the 8th century, adjacent village compounds called ile coalesced into numerous territorial city-states in which clan loyalties became subordinate to dynastic chieftains. Urbanization was accompanied by high levels of artistic achievement, particularly in terracotta and ivory sculpture and in the sophisticated metal casting produced at Ife.

The Yoruba pay tribute to a pantheon composed of a Supreme Deity, Olorun and the Orisha. The Olorun is now called God in the Yoruba language. There are 400 deities called Orisha who perform various tasks. According to the Yoruba, Oduduwa is regarded as the ancestor of the Yoruba kings. According to one of the various myths about him, he founded Ife and dispatched his sons and daughters to establish similar kingdoms in other parts of what is today known as Yorubaland. The Yorubaland now consists of different tribes from different states which are located in the Southwestern part of the country, states like Oyo State, Ondo State, Ekiti State, Ogun State, among others.

Igbo Kingdom[edit]

Nri Kingdom[edit]

The Kingdom of Nri is considered to be the foundation of Igbo culture, and the oldest Kingdom in Nigeria.[7] Nri and Aguleri, where the Igbo creation myth originates, are in the territory of the Umueri clan, who trace their lineages back to the patriarchal king-figure, Eri.[8] Eri's origins are unclear, though he has been described as a "sky being" sent by Chukwu (God).[8][9] He has been characterized as having first given societal order to the people of Anambra.[9]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Nri hegemony in Igboland may go back as far as the 9th century,[10] and royal burials have been unearthed dating to at least the 10th century. Eri, the god-like founder of Nri, is believed to have settled the region around 948 with other related Igbo cultures following after in the 13th century.[11] The first Eze Nri (King of Nri), Ìfikuánim, followed directly after him. According to Igbo oral tradition, his reign started in 1043.[12] At least one historian puts Ìfikuánim's reign much later, around 1225.[13]

The Kingdom of Nri was a religio-polity, a sort of theocratic state, that developed in the central heartland of the Igbo region.[11] The Nri had a taboo symbolic code with six types. These included human (such as the birth of twins), animal (such as killing or eating of pythons),[15] object, temporal, behavioral, speech and place taboos.[16] The rules regarding these taboos were used to educate and govern Nri's subjects. This meant that, while certain Igbo may have lived under different formal administration, all followers of the Igbo religion had to abide by the rules of the faith and obey its representative on earth, the Eze Nri.[15][16]

Decline of Nri kingdom[edit]

With the decline of Nri kingdom in the 15th to 17th centuries, several states once under their influence, became powerful economic oracular oligarchies and large commercial states that dominated Igboland. The neighboring Awka city-state rose in power as a result of their powerful Agbala oracle and metalworking expertise. The Onitsha Kingdom, which was originally inhabited by Igbos from east of the Niger, was founded in the 16th century by migrants from Anioma (Western Igboland). Later groups like the Igala traders from the hinterland settled in Onitsha in the 18th century. Western Igbo kingdoms like Aboh, dominated trade in the lower Niger area from the 17th century until European penetration. The Umunoha state in the Owerri area used the Igwe ka Ala oracle at their advantage. However, the Cross River Igbo state like the Aro had the greatest influence in Igboland and adjacent areas after the decline of Nri.

The Arochukwu kingdom emerged after the Aro-Ibibio Wars from 1630 to 1720, and went on to form the Aro Confederacy which economically dominated Eastern Nigerian hinterland. The source of the Aro Confederacy's economic dominance was based on the judicial oracle of Ibini Ukpabi ("Long Juju") and their military forces which included powerful allies such as Ohafia, Abam, Ezza, and other related neighboring states. The Abiriba and Aro are Brothers whose migration is traced to the Ekpa Kingdom in East of Cross River; their exact take of location was at Ekpa (Mkpa) east of the Cross River. They crossed the river to Urupkam (Usukpam) west of the Cross River and founded two settlements: Ena Uda and Ena Ofia in present-day Erai. Aro and Abiriba cooperated to become a powerful economic force.

Igbo gods, like those of the Yoruba, were numerous, but their relationship to one another and human beings was essentially egalitarian, reflecting Igbo society as a whole. A number of oracles and local cults attracted devotees while the central deity, the earth mother and fertility figure Ala, was venerated at shrines throughout Igboland.

The weakness of a popular theory that Igbos were stateless rests on the paucity of historical evidence of pre-colonial Igbo society. There is a huge gap between the archaeological finds of Igbo Ukwu, which reveal a rich material culture in the heart of the Igbo region in the 8th century, and the oral traditions of the 20th century. Benin exercised considerable influence on the western Igbo, who adopted many of the political structures familiar to the Yoruba-Benin region, but Asaba and its immediate neighbors, such as Ibusa, Ogwashi-Ukwu, Okpanam, Issele-Azagba and Issele-Ukwu, were much closer to the Kingdom of Nri. Ofega was the queen for the Onitsha Igbo.Igbo imabana

Oyo and Benin[edit]

During the 15th century Oyo and Benin surpassed Ife as political and economic powers, although Ife preserved its status as a religious center. Respect for the priestly functions of the oni of Ife was a crucial factor in the evolution of Yoruban culture. The Ife model of government was adapted at Oyo, where a member of its ruling dynasty controlled several smaller city-states. A state council (the Oyo Mesi) named the Alaafin (king) and acted as a check on his authority. Their capital city was situated about 100 km north of present-day Oyo. Unlike the forest-bound Yoruba kingdoms, Oyo was in the savanna and drew its military strength from its cavalry forces, which established hegemony over the adjacent Nupe and the Borgu kingdoms and thereby developed trade routes farther to the north.

The Benin Empire (1440–1897; called Bini by locals) was a pre-colonial African state in what is now modern Nigeria. It should not be confused with the modern-day country called Benin, formerly called Dahomey.

Northern kingdoms of the Sahel[edit]

Trade is the key to the emergence of organized communities in the sahelian portions of Nigeria. Prehistoric inhabitants adjusting to the encroaching desert were widely scattered by the third millennium BC, when the desiccation of the Sahara began. Trans-Saharan trade routes linked the western Sudan with the Mediterranean since the time of Carthage and with the Upper Nile from a much earlier date, establishing avenues of communication and cultural influence that remained open until the end of the 19th century. By these same routes, Islam made its way south into West Africa after the 9th century.

By then a string of dynastic states, including the earliest Hausa states, stretched into western and central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and Kanem, which were not within the boundaries of modern Nigeria but which influenced the history of the Nigerian savanna. Ghana declined in the 11th century but was succeeded by the Mali Empire which consolidated much of western Sudan in the 13th century.

Following the breakup of Mali, a local leader named Sonni Ali (1464–1492) founded the Songhai Empire in the region of middle Niger and western Sudan and took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sonni Ali seized Timbuktu in 1468 and Djenné in 1473, building his regime on trade revenues and the cooperation of Muslim merchants. His successor Askia Muhammad Ture (1493–1528) made Islam the official religion, built mosques, and brought Muslim scholars, including al-Maghili (d.1504), the founder of an important tradition of Sudanic African Muslim scholarship, to Gao.[17]

Although these western empires had little political influence on the Nigerian savanna before 1500 they had a strong cultural and economic impact that became more pronounced in the 16th century, especially because these states became associated with the spread of Islam and trade. Throughout the 16th-century much of northern Nigeria paid homage to Songhai in the west or to Borno, a rival empire in the east.

Kanem-Bornu Empire[edit]

Borno's history is closely associated with Kanem, which had achieved imperial status in the Lake Chad basin by the 13th century. Kanem expanded westward to include the area that became Borno. The mai (king) of Kanem and his court accepted Islam in the 11th century, as the western empires also had done. Islam was used to reinforce the political and social structures of the state although many established customs were maintained. Women, for example, continued to exercise considerable political influence.

The mai employed his mounted bodyguard and an inchoate army of nobles to extend Kanem's authority into Borno. By tradition, the territory was conferred on the heir to the throne to govern during his apprenticeship. In the 14th century, however, dynastic conflict forced the then-ruling group and its followers to relocate in Borno, where as a result the Kanuri emerged as an ethnic group in the late 14th and 15th centuries. The civil war that disrupted Kanem in the second half of the 14th century resulted in the independence of Borno.

Borno's prosperity depended on the trans-Sudanic slave trade and the desert trade in salt and livestock. The need to protect its commercial interests compelled Borno to intervene in Kanem, which continued to be a theater of war throughout the 15th century and into the 16th century. Despite its relative political weakness in this period, Borno's court and mosques under the patronage of a line of scholarly kings earned fame as centers of Islamic culture and learning.

De-colonial states, 1800–1948[edit]

Savanna states[edit]

During the 16th century, the Songhai Empire reached its peak, stretching from the Senegal and Gambia rivers and incorporating part of Hausaland in the east. Concurrently the Saifawa Dynasty of Borno conquered Kanem and extended control west to Hausa cities not under Songhai authority. Largely because of Songhai's influence, there was a blossoming of Islamic learning and culture. Songhai collapsed in 1591 when a Moroccan army conquered Gao and Timbuktu. Morocco was unable to control the empire and the various provinces, including the Hausa states, became independent. The collapse undermined Songhai's hegemony over the Hausa states and abruptly altered the course of regional history.

Borno reached its pinnacle under mai Idris Aloma (ca. 1569–1600) during whose reign Kanem was reconquered. The destruction of Songhai left Borno uncontested and until the 18th-century Borno dominated northern Nigeria. Despite Borno's hegemony the Hausa states continued to wrestle for ascendancy. Gradually Borno's position weakened; its inability to check political rivalries between competing Hausa cities was one example of this decline. Another factor was the military threat of the Tuareg centered at Agades who penetrated the northern districts of Borno. The major cause of Borno's decline was a severe drought that struck the Sahel and savanna from in the middle of the 18th century. As a consequence, Borno lost many northern territories to the Tuareg whose mobility allowed them to endure the famine more effectively. Borno regained some of its former might in the succeeding decades, but another drought occurred in the 1790s, again weakening the state.

Ecological and political instability provided the background for the jihad of Usman dan Fodio. The military rivalries of the Hausa states strained the region's economic resources at a time when drought and famine undermined farmers and herders. Many Fulani moved into Hausaland and Borno, and their arrival increased tensions because they had no loyalty to the political authorities, who saw them as a source of increased taxation. By the end of the 18th century, some Muslim ulema began articulating the grievances of the common people. Efforts to eliminate or control these religious leaders only heightened the tensions, setting the stage for jihad.[17]

According to the Encyclopedia of African History, "It is estimated that by the 1890s the largest slave population of the world, about 2 million people, was concentrated in the territories of the Sokoto Caliphate. The use of slave labor was extensive, especially in agriculture."[18]

Comments

Post a Comment